Whaleman's Memorial, Revisited

2017

Wood & stiffened muslin, charcoal on paper

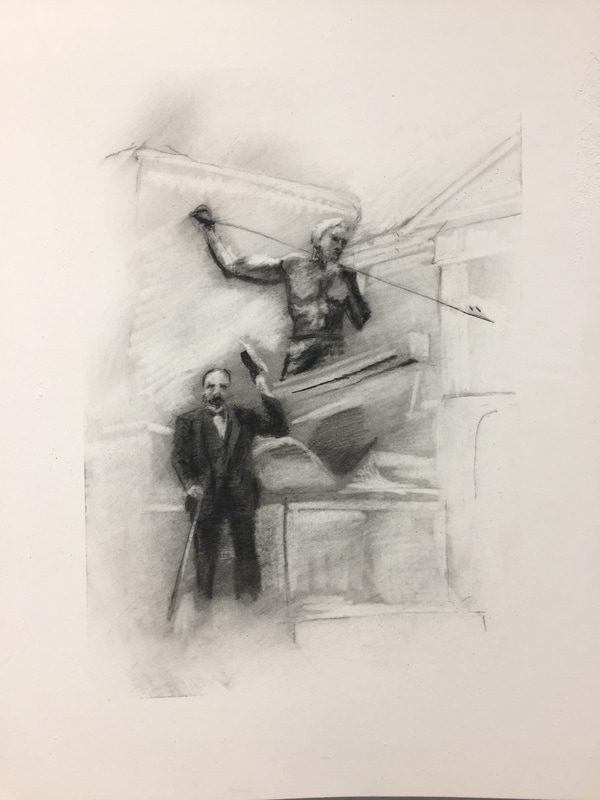

In 1913, the city of New Bedford, Massachusetts erected The Whaleman, a monument that reflected the city's historic whaling industry-based wealth and aggrandized the figure of the whaler as a mythic local hero. However, by this time in local history, whaling had given way to textile production as New Bedford's primary industry. In turn, New Bedford's prosperity became increasingly driven by the labor of immigrants and women who worked long hours in the unsafe conditions of the city's mills. Historical records illuminate the intent of William Crapo, the donor of the sculpture, in memorializing the mythic whaler - to assert a traditionally white male image of work in a city where the reality of labor no longer reflected this identity.

As such, the memorial's prominence in the center of the city hides the remnants of a woman and immigrant-dominated industry that kept New Bedford afloat after whaling was no longer profitable - at great personal cost. Even the image of the whaler is historically inaccurate - despite most harpooners being of Cape Verdean or Wampanoag origin, Crapo insisted that the model for the monument be white. This fictional view of manhood also ignored the messy realities of whalemen's work and the environmental toll commercial whaling enacted on marine life.

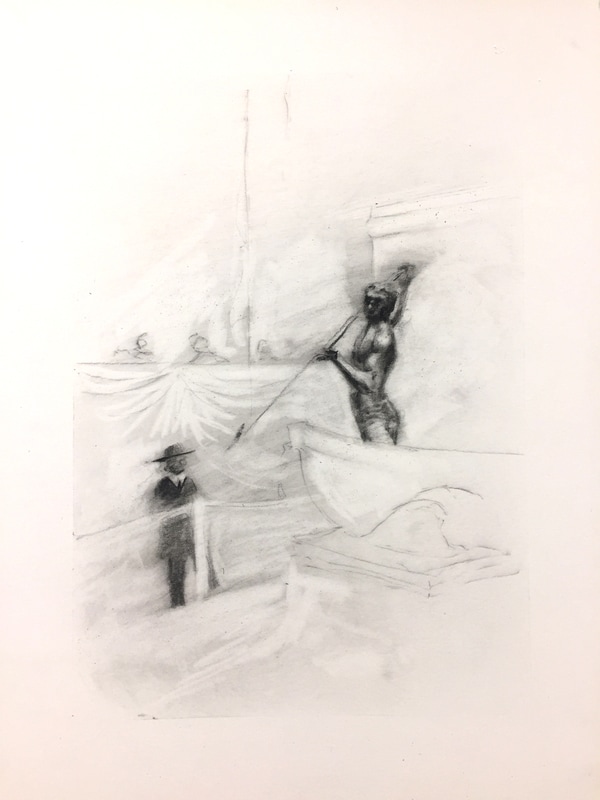

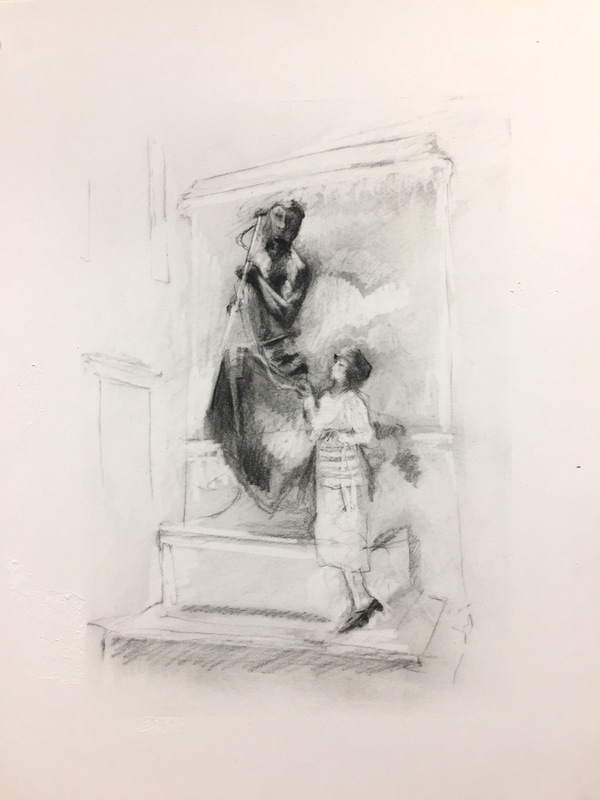

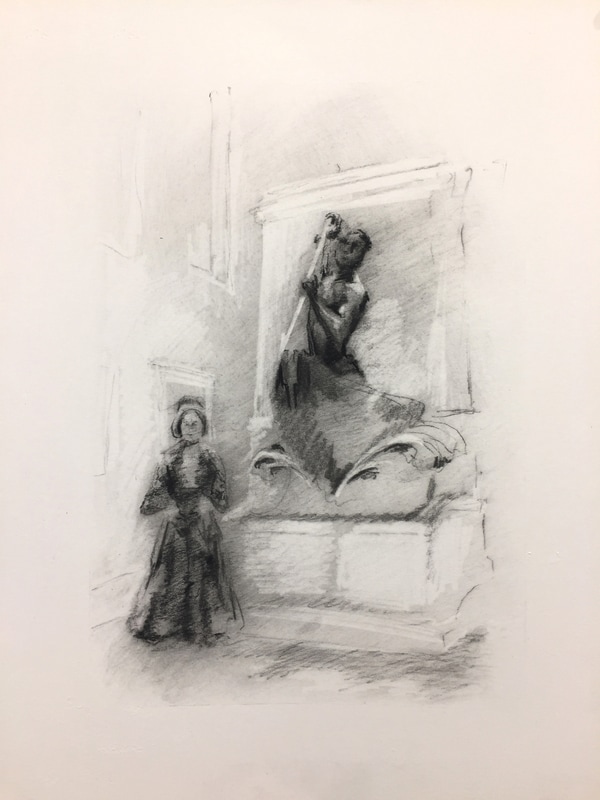

The following works revisit the memorial, stripping it to its structure to examine its inner narratives. An accompanying series of drawings references photographs of visitors interacting with the memorial at its opening as well as photojournalist Lewis Hines' documentation of child laborers in the city's textile mills.

2017

Wood & stiffened muslin, charcoal on paper

In 1913, the city of New Bedford, Massachusetts erected The Whaleman, a monument that reflected the city's historic whaling industry-based wealth and aggrandized the figure of the whaler as a mythic local hero. However, by this time in local history, whaling had given way to textile production as New Bedford's primary industry. In turn, New Bedford's prosperity became increasingly driven by the labor of immigrants and women who worked long hours in the unsafe conditions of the city's mills. Historical records illuminate the intent of William Crapo, the donor of the sculpture, in memorializing the mythic whaler - to assert a traditionally white male image of work in a city where the reality of labor no longer reflected this identity.

As such, the memorial's prominence in the center of the city hides the remnants of a woman and immigrant-dominated industry that kept New Bedford afloat after whaling was no longer profitable - at great personal cost. Even the image of the whaler is historically inaccurate - despite most harpooners being of Cape Verdean or Wampanoag origin, Crapo insisted that the model for the monument be white. This fictional view of manhood also ignored the messy realities of whalemen's work and the environmental toll commercial whaling enacted on marine life.

The following works revisit the memorial, stripping it to its structure to examine its inner narratives. An accompanying series of drawings references photographs of visitors interacting with the memorial at its opening as well as photojournalist Lewis Hines' documentation of child laborers in the city's textile mills.